- October 20, 2025

Program Notes: Poulenc's Gloria

John Koegel

John Koegel

Professor of Musicology

California State University, Fullerton

Poulenc's Gloria

Francis Poulenc (1899-1963) was one of the most prominent composers of the twentieth century who, along with Olivier Messiaen, was also one of the most important French composers of sacred music. His Gloria for chorus, soprano soloist, and orchestra is one of his most frequently performed pieces and one of the principal choral-orchestral repertory works. Besides his Gloria and numerous other choral works Poulenc is noted for his many beautiful French art songs and his substantial number of important piano compositions, as well as orchestral and chamber works, several operas (especially Dialogues des Carmélites), and several film scores.

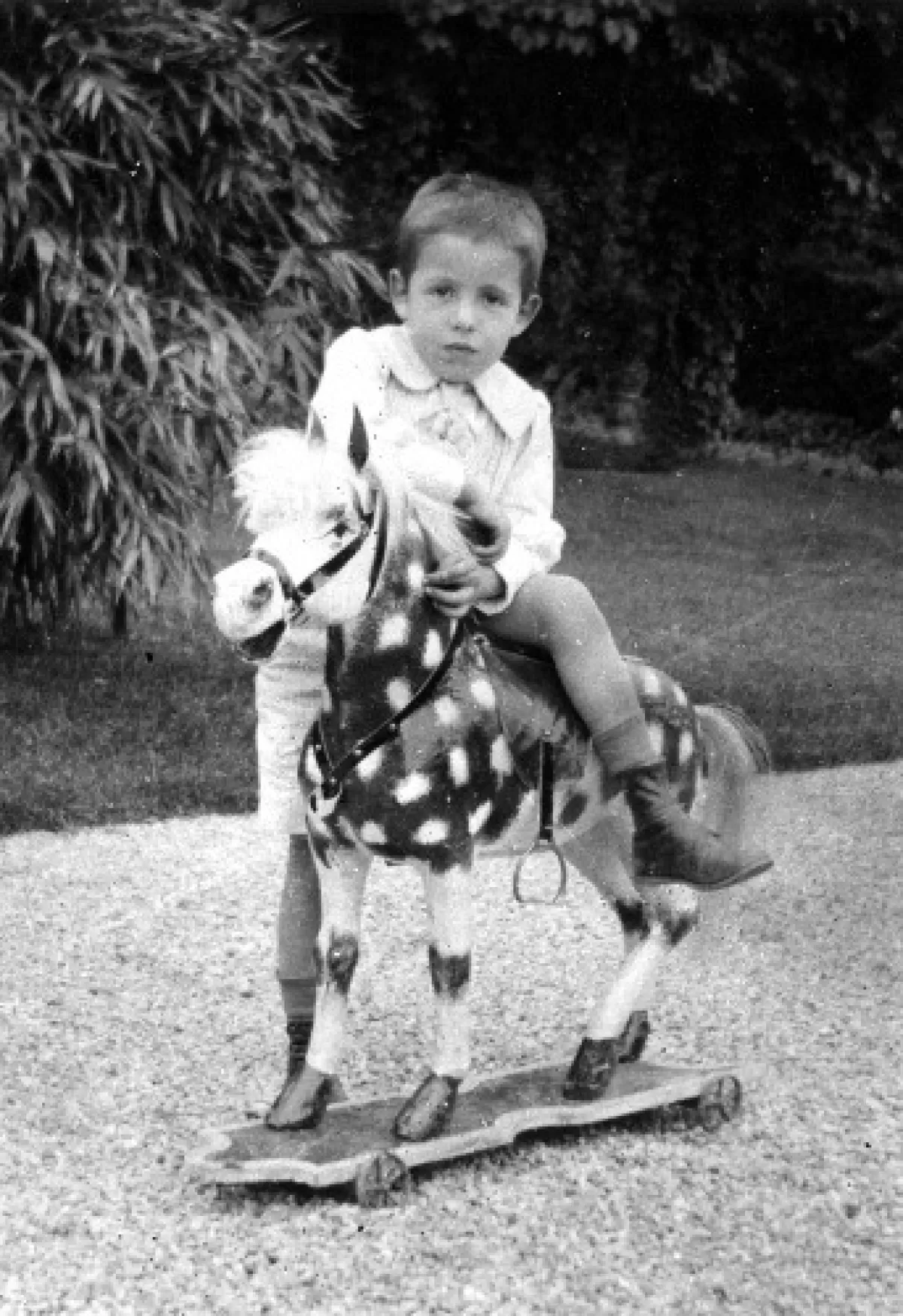

Born in Paris into a wealthy French family—his father was a director of a family pharmaceutical company—he had roots in the department of Aveyron in the south with his father’s family, and in Paris with his mother’s family. He associated his Catholic faith with his father’s origins in Aveyron and attributed his artistic interests to his mother, who introduced him to the piano. Poulenc’s father insisted that his son be given a formal classical education, and in return allowed him to study music. Most unfortunately, he lost his parents early: his mother died when he was 16 and his father when he was 18.

Born in Paris into a wealthy French family—his father was a director of a family pharmaceutical company—he had roots in the department of Aveyron in the south with his father’s family, and in Paris with his mother’s family. He associated his Catholic faith with his father’s origins in Aveyron and attributed his artistic interests to his mother, who introduced him to the piano. Poulenc’s father insisted that his son be given a formal classical education, and in return allowed him to study music. Most unfortunately, he lost his parents early: his mother died when he was 16 and his father when he was 18.

During World War I Poulenc studied piano with the famous Spanish piano virtuoso and teacher Ricardo Viñes, who became his mentor and the first performer of his earliest works for the piano. Viñes’s influence led to him becoming a composer and he introduced Poulenc to important musicians active in Paris at the time, such as composers Georges Auric, Erik Satie and Manuel de Falla. His public recital debut took place in Paris in 1917, with his vocal-chamber work Rapsodie nègre, dedicated to Satie. Conscripted into military service in 1918, he continued to compose during that time, including his successful Trois mouvements perpétuels and Le bestiaire, his song cycle on poems by Guillaume Apollinaire. Poulenc also briefly studied composition with Charles Koechlin. In essence, however, he was mostly a self-taught composer with a variety of musical influences.

As the composer himself stated, “my gods are Bach, Mozart, Haydn, Chopin, Stravinsky, and Mussorgsky. You may say, what a concoction! But that’s how I like music: taking my models everywhere, from what pleases me.”

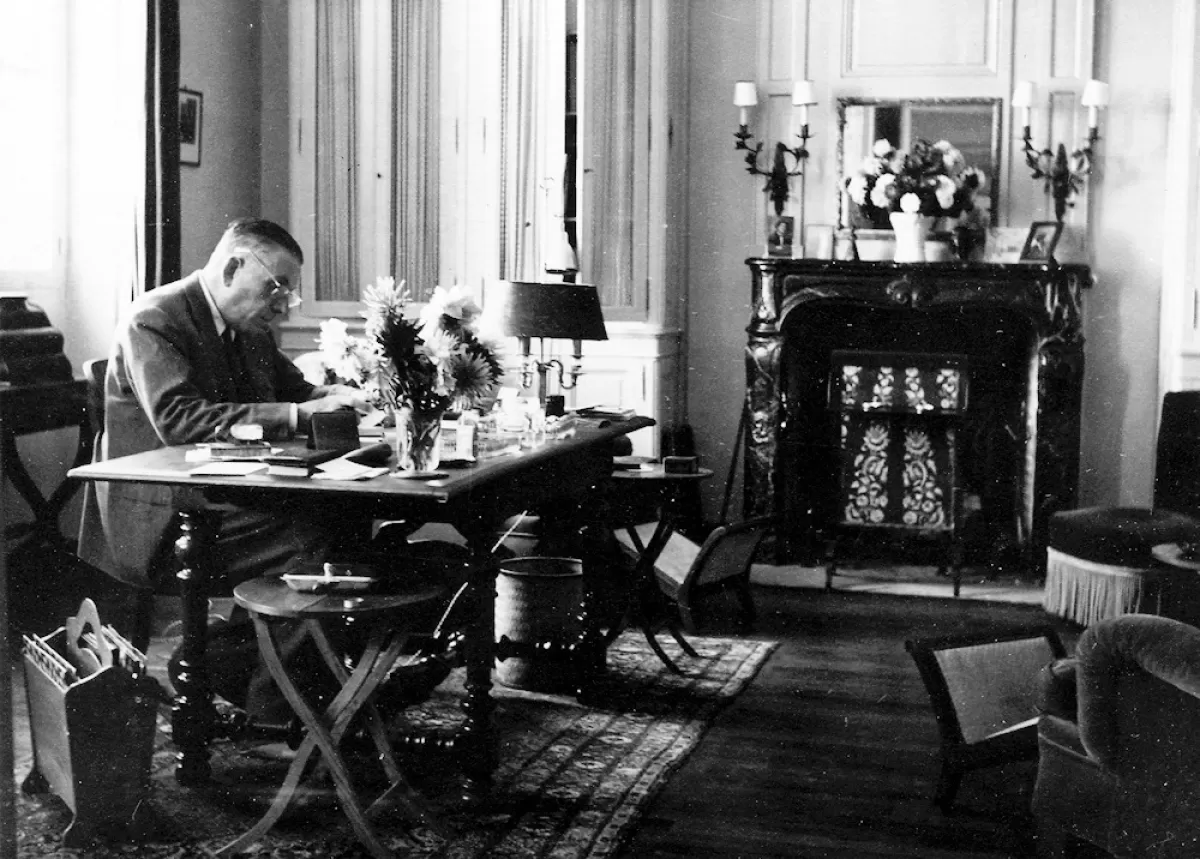

In the heady 1920s in post-war Paris, Poulenc moved widely throughout the city’s artistic circles, becoming part of Satie’s group Les nouveaux jeunes (The New Young People), which would later become Les Six, the group of six French and French-Swiss composers who had strong ideas about which direction French art music should follow, especially rejecting the influence of German music. Besides Poulenc, the group consisted of George Auric, Louis Durey, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud, and Germaine Tailleferre. His career accelerated when in 1924 Serge Diaghilev, impresario of the famous Ballets Russes, commissioned him to write a ballet score for his company. Poulenc’s music for Les biches was a great success and helped cement his status as one of France’s leading young composers. Poulenc’s contributions to the French art song were substantial and his songs are firmly part of the core repertory of classical art songs. In 1934 he began an artistic association with the French baritone Pierre Bernac, for whom he composed some 90 art songs that they performed together in their song recitals over a 25-year period.

In the heady 1920s in post-war Paris, Poulenc moved widely throughout the city’s artistic circles, becoming part of Satie’s group Les nouveaux jeunes (The New Young People), which would later become Les Six, the group of six French and French-Swiss composers who had strong ideas about which direction French art music should follow, especially rejecting the influence of German music. Besides Poulenc, the group consisted of George Auric, Louis Durey, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud, and Germaine Tailleferre. His career accelerated when in 1924 Serge Diaghilev, impresario of the famous Ballets Russes, commissioned him to write a ballet score for his company. Poulenc’s music for Les biches was a great success and helped cement his status as one of France’s leading young composers. Poulenc’s contributions to the French art song were substantial and his songs are firmly part of the core repertory of classical art songs. In 1934 he began an artistic association with the French baritone Pierre Bernac, for whom he composed some 90 art songs that they performed together in their song recitals over a 25-year period.

Scholars see two main strands represented in Poulenc’s music: the sacred and the profane. If his works of the 1920s represent the profane, works composed in the 1930s and later represent his interest in the sacred. The death of a close friend in 1935 and his pilgrimage to the Black Virgin at the Sanctuaire Notre-Dame de Rocamadour in southwestern France in 1936 revived his Catholic faith and led him to compose sacred choral works, including his setting of the Stabat Mater text and his Litanies à la vierge noire. Indeed, the sacred and profane in Poulenc’s music were encapsulated by French musicologist and music critic Claude Rostand in his famous remark: “In Poulenc there is something of the monk and something of the rascal.” American composer Ned Rorem was quoted as saying that Poulenc was “a whole man always interlocking soul and flesh, sacred and profane.”

Poulenc’s Gloria was composed between May and December 1959 on commission from the Koussevitzky Foundation. The foundation originally requested a symphony, then an organ concerto, but Poulenc preferred instead to fulfill the commission with his Gloria. It was first performed in 1961 by the Boston Symphony under conductor Charles Munch, with the Chorus Pro Musica. It sets the Gloria section of the Roman Catholic Mass Ordinary, in six individual, relatively brief movements, each with its own distinct musical character. Criticized by some listeners of the time for the juxtaposition of the sacred and profane in the work, and because of its combination of seriousness and lightheartedness, Poulenc intended the Gloria as a concert piece rather than as part of a liturgical Mass celebration.

Poulenc’s Gloria was composed between May and December 1959 on commission from the Koussevitzky Foundation. The foundation originally requested a symphony, then an organ concerto, but Poulenc preferred instead to fulfill the commission with his Gloria. It was first performed in 1961 by the Boston Symphony under conductor Charles Munch, with the Chorus Pro Musica. It sets the Gloria section of the Roman Catholic Mass Ordinary, in six individual, relatively brief movements, each with its own distinct musical character. Criticized by some listeners of the time for the juxtaposition of the sacred and profane in the work, and because of its combination of seriousness and lightheartedness, Poulenc intended the Gloria as a concert piece rather than as part of a liturgical Mass celebration.

The composer recalled that: “The second movement caused a scandal; I wonder why? I was simply thinking, in writing it, of the Gozzoli frescoes in which the angels stick out their tongues; I was thinking also of the serious Benedictines whom I saw playing soccer one day.”

Poulenc uses a variety of musical devices in his Gloria, including unaccompanied a cappella sections, swift tempo changes, unexpected harmonic modulations, a great sense of rhythmic vitality, motivic repetition that unifies the work, a weaving together of soloist, chorus, and orchestra in the “Domine Deus” movement, and crisp instrumental and vocal writing. According to musicologist Roger Nichols, in the Gloria, “the choral writing is unsanctimonious to the point of willfulness, as in the stressing of the phrase ‘Gloria in excelsis Deo,’ while the ostinatos, the soaring soprano and the matchless tunes proclaim Poulenc a believer who had, in [British composer Michael] Tippett’s phrase, ‘contracted in to abundance.’”

Hear Pacific Chorale and Pacific Symphony under the baton of Robert Istad in concert at this one-time-only performance on October 25. Reserve your ticket today.